Highlights from the TOKI Auction by Phillips Hong Kong

On November 22, an auction took place in Hong Kong that will go down in the history of Japanese watchmaking. The famous Phillips auction house organized one of its secret sales, but on a never-before-seen theme: Japan.

Let’s take a look back at some of the watches on display and discuss the results of this exceptional sale.

Note : Unless otherwise stated, all photos are from Phillips.com and are the property of Phillips HK.

On November 22, an auction was held in Hong Kong that will go down in the history of Japanese watchmaking. The famous auction house Phillips organized one of its signature sales, but with a theme never before seen : Japan.

Calligraphy created live by the artist Mamimozi on a 2.10m x 2.10m canvas, sold for $17,950.

The name TOKI comes from the kanji 刻, one of whose meanings is "time." This character also means "to engrave," and as you will see, the two meanings are connected : on Japanese clocks (the famous wadokei), the days were divided into 12 periods for daytime and 12 periods of night time, each represented by a sign of the Chinese zodiac. The length of these periods was not fixed but changed with the seasons, known as "temporal hours." On the wadokei, each of these temporal hours was marked by a small engraved plaque with the corresponding zodiac sign. In other words, each engraving represented an hour. And as you might have guessed, these temporary hours were called TOKI in Japanese. Now you can understand why the same kanji can be used to refer to both engraving and time!

But let's get back to this Japan-themed auction.

The auction revolves around the theme of Japan, with broadly speaking four types of watches offered :

Watches from Japanese collectors

Watches made for the Japanese market

Watches from established Japanese brands

Watches by independent Japanese watchmakers

I won't go into detail about the first two categories, but I encourage you to visit the dedicated auction page on the Phillips website to get an idea. From the simple Rolex Explorer to the Vianney Halter, including the Patek "Kimono" in cloisonné enamel, De Bethune, or exceptional pocket watches, the selection of watches presented leaves no doubt about the excellence and the level of Japanese collectors !

Since I am not very familiar with these watches and their market, I prefer to leave it to those who know to speak on the subject. However, I think it is worth taking a closer look at the other two categories. So let’s go through each watch that was offered and discuss the prices that were reached.

Watches from established Japanese Brands

The three major names in Japanese watchmaking were, of course, represented : Casio, Citizen, and Seiko.

Casio

The sole representative of Casio is, as you might expect, an exceptional watch : the reference G-D5000-9JR. Doesn't ring a bell ? It's simply a G-Shock... in solid 18-karat gold !

Released in 35 pieces for the 35th anniversary of G-Shock, this watch, more appropriately called the G-Shock Dream Project "Pure Gold," was allocated via a raffle to Japanese collectors in May 2019. Against all odds, it sold extremely quickly despite the hefty price tag of $70,000 and a weight of 297g—approximately $235 per gram !

You might be surprised that such a watch sold so well, but you may be even more surprised to learn that it sold at auction for around $146,800—just over double its retail price !

An impressive performance for this watch, which I believe is the most expensive Casio ever sold !

If you happen to have $146,800 to invest in Casio, note that you could instead buy one FW91 per day for 19 years. The choice is yours...

Citizen

Citizen also had just one representative, but it’s a good one: the AQ6110-10L. This watch is part of "The Citizen" collection and features the renowned Caliber 0100 quartz movement, celebrated for its mind-blowing accuracy of +/- 1 second per year. What sets this model apart is its dial, crafted from washi paper and hand-dyed with natural indigo in Tokushima—the birthplace of Aizome (indigo dyeing). Here, the last remaining artisans still cultivate and ferment the indigo flowers by hand.

This is a more common model released in late 2022, priced at ¥880,000 in Japan, which is currently approximately €5,877 (as of November 2024).

This one sold for $3,578, which seems to be a great deal for the buyer.

Since Citizen rarely offers, to my knowledge, particularly expensive or extravagant pieces like the solid gold Casio, it was probably difficult to find a watch that could ignite the bidders' spending frenzy. One might have hoped to see the Citizen tourbillon created by Hajime Asaoka, but unfortunately, that wasn’t the case. The final price was slightly above Phillips' estimates, but as those are notoriously very low, there isn’t much to say about this rather unremarkable result for Citizen.

Seiko

Unsurprisingly, Seiko is by far the most well-represented Japanese brand in this auction, with no fewer than 9 pieces.

Vintage Seiko

Among the vintage selection, four standout models are featured.

Seikosha Tensoku

If you're already a reader of Wadokei, you're familiar with this watch. If not, I encourage you to read this article.

The model offered for sale appears to be in very good condition. It is the later version with a 9 jewels movement. To my surprise, it sold for just slightly above its estimate, at around $10,600, which is roughly the market price for this model.

In hindsight, China might not have been the ideal place to set a record price for a watch originally designed for the Imperial Japanese Army...

Seiko Astronomical Observatory Chronometer

Whether you call it the 45GSN, 45AOC, or Astronomical Observatory Chronometer, this watch is one of the legends in Seiko's history! After Seiko's victory in the Geneva and Neuchâtel chronometry trials in 1968, the Neuchâtel Observatory continued to accept, test, and certify movements. Seiko sent 103 Caliber 4520A movements, of which 73 passed the observatory’s very stringent tests. Rather than keeping this achievement under wraps or storing the movements away, Seiko decided to encase them in a unique watch entirely crafted in gold, featuring an impressive textured finish on the dial and case—despite the fact that these movements were not typically intended for commercial use. Very few brands did so in the past and those Observatory pieces are very rare across the board.

In 1969, 25 out of 30 movements were certified, followed by 128 out of 150 in 1970, resulting in a total of 226 45GSN watches produced and sold over a period of three years. If you’re interested in this topic, I highly recommend Anthony Kable's detailed article.

The watch presented at the auction had been displayed for a few months at the Seiko Museum in Tokyo. The mainspring cover shows significant signs of oxidation, and photos from Hodinkee reveal a relatively oxidized dial (something that wasn’t apparent in the Phillips photos). These details likely explain the final price of $57,122, which falls within the average range one might expect for this legendary piece in the brand’s history. A solid result, though not particularly noteworthy.

Grand Seiko VFA Day-date

I believe the VFA hardly needs an introduction. This particular piece belonged to Mark Cho, of The Armoury, and was featured in the famous book A Man and His Watch. The case appears to be unpolished, but the crystal is not original, and the dial shows some signs of oxidation. As the day-date version is the rarest and most sought-after, I was curious to see whether the watch’s provenance would offset its minor flaws.

It sold for $29,377, which is a very high price for a 6186 VFA. However, as it’s becoming increasingly difficult to find one in good condition, I believe prices will steadily rise over the coming years. With that said, this remains an excellent result, likely driven by its previous ownership.

Seiko Divers 6215-7000

A missing link between the 62MAS and the famous professional diver 6159 (the predecessor of the MM300), the 6215-7000 is one of the most coveted vintage diver models among collectors. In excellent condition, with a well-preserved bezel insert and no oxidation on the indices or hands (although I suspect the hour hand has been re-lumed), and equipped with a replacement crystal (the original appears to be included with the sale), it sold for $8,160. This is roughly the market price—or even a decent deal, considering its condition and the inclusion of the original crystal.

Modern Grand Seiko

SBGW239

Released in platinum to commemorate Seiko's 130th anniversary in 2011, this watch—also from Mark Cho's personal collection—is truly a piece for Grand Seiko enthusiasts. This is the platinum version of the famous SBGW033, and it can be interesting to draw a comparison between this model and the original platinum "First" from 1960, one of the rarest watches in Seiko’s history. Even more interesting is that this modern version shares the same dimensions as the original, making it arguably the finest modern reissue of the classic.

Its sale price of $17,950 isn’t particularly impressive either, as it aligns roughly with what one might expect to pay for this watch on the second-hand market. A similar piece sold in Geneva in 2019 for slightly more ($21,100 at the current exchange rate). It’s not a particularly remarkable result, but it doesn’t come as a surprise, given that the small and understated design of this watch is quite far from Grand Seiko’s current style trends.

SBGZ009

Masterpiece from the Micro Artist Studio, this watch features a hand-engraved platinum case, white gold hands and indices, and a movement with exceptional finishing (hand beveling, sharp interior angle, etc.). It represents the pinnacle of what Grand Seiko has to offer.

Originally priced at $79,000, it sold at auction for $57,120—a great deal for the buyer but a disappointing result for the brand, especially considering the fact that Phillips prices typically exceed market value!

Credor

GBLR99 aka Eichi I

While the Credor Eichi II is now well-known among enthusiasts, the Eichi I, released in 2008 in only 25 pieces, remains far more discreet. Smaller in size, with a more intricate porcelain dial crafted by the renowned Noritake, a German silver movement, and numerous other unique details, this model is almost never seen on the market. It surpasses the current Eichi II not only in rarity but also, depending on whom you ask, in the choice of details !

The price achieved by this watch is likely the biggest surprise of this auction, as the hammer fell at approximately $258,500 !

For reference, the price of the Credor Eichi in 2008, at the current exchange rate, was approximately $39,000.

The result achieved by this Eichi underscores the mythical and exceedingly rare nature of this version, already highly sought after by collectors, and firmly establishes it in the pantheon of Japanese watches !

GBLQ998

The Credor Sonnerie is one of the most intriguing and complex watches ever produced by Seiko. With its skeletonized movement housed in a miniature version of a Japanese orin bell (or Buddhist bowl), this Spring Drive model, released in 2006, still remains in the catalog as of today (unlike the minute repeater). Its price has stayed unchanged, hovering around $140,000. The auction price of $81,600 is therefore not a very positive signal. While this auction made the buyer happy, it clear isn’t the case for the seller, who had purchased the watch just three years ago. Considering the price achieved by the Eichi, the fact that it’s a Spring Drive doesn’t fully explain this somewhat disappointing result !

GCBY997

Instead of its Star Wars like reference number, I prefer the unofficial name of this watch: Ryusei Raden. Ryusei means "meteor" or "shooting star," and Raden refers to the technique of embedding mother of pearl into lacquer.

This stunning Credor, equipped with the ultra-thin Caliber 68 and a magnificent dial is a limited edition of 60 pieces that was released in 2023 and cost about $11,000 in Japan. The auction price of over $27,750 is therefore a pleasant surprise, perhaps partially explained by the fact that this watch also belonged to Mark Cho. However, it does seem surprising that such a simple and very recent model sold for 2.5 times its retail price, while the Sonnerie went for only half of its catalog price!

And so, this concludes the results achieved by the major Japanese brands. While the Casio and Credor Eichi stand out for their exceptionally high prices, the rest is somewhat lackluster. Notably, the VFA and Mark Cho's Credor “Ryusei Raden” fetched strong prices, while the others saw average to low results. The two biggest surprises for me were the Credor Sonnerie and the Grand Seiko Masterpiece. At least one thing is clear : Seiko doesn't follow the Swiss brands’ playbook of artificially inflating auction prices by buying back their own watches !

Now, let's move on to the independent watchmakers.

Watches by Japanese Independent Watchmakers

Precision Watch Tokyo

I'll start by talking about Hajime Asaoka, because even though none of the watches presented here bear his name on the dial, he is the mastermind behind six of the lots featured in this sale.

As one of the pioneers of Japanese independent watchmaking, his name is likely familiar to you. While he has crafted exceptional tourbillons both under his own name and for Citizen, he has gained wider recognition since the creation of his far more accessible brand : Kurono Tokyo.

He currently leads Precision Watch Tokyo (PWT), a company encompassing four brands:

Hajime Asaoka: His high-end independent brand.

Otsuka Lotec: Founded by Jiro Katayama, who recently received the GPHG's Challenge Prize.

Takano : A historic Japanese brand now owned by Ricoh, for which PWT has obtained a license to use the name.

Kurono Tokyo: A brand that needs no introduction.

Kurono Tokyo Grand Niji

Kurono Tokyo presented a unique model named Grand Niji, marking the brand’s first watch with a gold case. Its dial is crafted with lacquer by the artist Megumi Shimamoto, with whom the brand has previously collaborated. The technique used involves applying multiple layers, resulting in an absolutely mesmerizing glittery rainbow effect!

With a price of nearly €29,400, I think this is a positive signal for the brand, which is more accustomed to offering steel watches at a significantly lower price point. I must admit, I was expecting a slightly higher result, but it remains a solid outcome given the basic caliber used and the brand's usual positioning.

Kurono Tokyo Chronograph 2

The second Kurono in the auction was not provided by the brand, as the Chronograph 2 was released in 2021. This 38mm automatic chronograph, equipped with the classic Seiko/Time Module NE86 movement and featuring the brand's signature design, sold for approximately $5,700. While this is a high price, it’s not unreasonable considering that the brand's chronographs typically trade for between $3,000 and $4,000.

Takano Chateau Nouvel

Hajime Asaoka recently announced the revival of the Takano brand, which has been dormant for most of the last 60 years. The style closely resembles that of Kurono Tokyo, likely reflecting Asaoka's design influence, but the positioning is clearly different. Featuring a Zaratsu-polished case and certification from the Besançon Observatory for its Miyota movement, the new chronometer will be offered for sale at approximately $5,880 in Japan.

The unique model offered at the auction features a pink dial in a shade known in Japan as toki-iro, literally "the color of the Japanese ibis." Interestingly, the word ibis in Japanese is pronounced toki, making it a homophone of the day's auction theme.

And to everyone's surprise, this watch sold for just over €27,550 ! This will undoubtedly serve as excellent publicity for the newest brand in Hajime Asaoka's stable !

Otsuka Lotec

Otsuka Lotec is a young brand on the rise ! When I first discovered it about two years ago, Jiro Katayama was still making his watches alone in his small workshop in the Otsuka neighbourhood of Tokyo, as he had been doing since 2008. There was little to no information available online, watches seemed to only be available occasionally, when a new batch was completed, and they seemed to sell very quickly. Unsurprisingly, there was also no communication in English.

It turns out that in 2022, I was clearly not the only one to discover this brand!

Jiro Katayama

Credit: otsuka-lotec.com

It’s in 2022 that Hajime Asaoka discovered Jiro Katayama’s work as one of his employees had bought one of his watches. Asaoka decided to invest in Otsuka Lotec and brought the brand under the PWT umbrella.

Katayama continues to work on prototypes in his workshop and now oversees production with PWT's watchmakers. Despite the difficulty of obtaining one of these watches—requiring Japanese residency and a local credit card to participate in raffles—the brand gained popularity in 2023, notably through Swiss Watch Gang, and further in 2024, culminating in winning the GPHG's Challenge Prize this fall.

In this favorable context, three watches were presented at the auction.

N°6 Shinonome

Its name means "the sky just before dawn." This is the No. 6 model (awarded at the GPHG) featuring a semi-transparent dial and a blackened stainless steel case. The base model, equipped with a Miyota movement and an in-house module, costs approximately $2,900 in Japan. However, it seems the GPHG award significantly boosted the auction result, as this unique piece created specifically for the auction sold for nearly $68,500!!!

N°6

In addition to the Shinonome version, a classic No. 6 was put up for sale by its original owner, who had purchased it this past April and managed to make quite a profit, as it sold for just over $60,000!!!

N°7.5

Finally, a third Otsuka Lotec from August 2023 was offered for sale. This time, it was a model with a different look but following the same principle: a classic Miyota movement topped with an in-house module. While the price was much lower than the two No. 6 models just mentioned, it still sold for $21,200—nearly 10 times its original price of $2,200.

It's a total triumph for Otsuka Lotec, which continues its remarkable year following its victory at the GPHG! Undoubtedly, one of the pleasant surprises of this auction !

I will conclude this section on the brands associated with Hajime Asaoka by noting that, under the initiative of Jiro Katayama, all proceeds from the sale of the three watches provided by Precision Watch Tokyo (the other three came directly from collectors) will be used to support the lacquer industry in Wajima, which was severely affected by an earthquake on January 1st 2024.

Naoya Hida type 1D-2

Naoya Hida is a well-known figure in the Japanese watchmaking world, having worked in the industry since 1990. After nearly 30 years of experience—first in sales and marketing, then as a distribution for FP Journe and Ralph Lauren Watch—he launched his own brand in 2018. Highly regarded by collectors, his small production of only a few dozen watches per year is in such high demand that allocations are determined by a lottery system !

Kosuke Fujita, watchmaker; Naoya Hida, CEO and brand creator; Keisuke Kano, engraver

Credit: naoyahidawatch.com

The model presented here is not strictly a unique piece : it is the 1D-2 model. However, the auction winner will have the opportunity to personalize their watch with a unique engraving, created in collaboration with Keisuke Kano, the brand's engraver.

If you’re one of the five lucky guys who will have the chance to purchase a 1D-2 directly from the brand in 2024/2025, it will cost you approximately $38,850. Clearly the demand is very high, as this very watch sold bfor just over $81,600 at the auction ! A clear sign of the popularity of this remarkable Japanese brand among collectors!

Let’s finish with my two (or should I say three) favorite watchmakers from this auction

Masahiro Kikuno

The first is someone I’ve admired for years, and he is by far my favorite watchmaker : Masahiro Kikuno. Despite his young age, he is the first Japanese independent watchmaker, as he started since 2011 and joining the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants (AHCI) in 2013. He became known for his Wadokei Revision, a modernized version of the wadokei clocks but offered for the first time as a wristwatch. As if this wasn’t enough, he crafts everything by hand using traditional techniques!

Masahiro Kikuno

Crédit: europastar.com

He presented two watches at the TOKI auction.

Masahiro Kikuno Tourbillon 2012

This is simply the first watch Masahiro Kikuno ever sold, back in 2012. A collector, captivated by Kikuno-san’s work, purchased a pair of tourbillons at Baselworld 2012 : one in silver and the other in rose gold. While the collector was too attached to part with the silver version, Kikuno-san initially refused to separate the pair. However, the collector insisted that Masahiro sell the rose gold version to fund his work on future creations.

This is an exceptional piece with very high sentimental value. It is accompanied by a photo book documenting all the stages of the watch's creation, crafted entirely by hand, using old traditional watchmaking techniques.

I was delighted to see that I’m clearly not the only one who admires Masahiro Kikuno’s work. Despite a very conservative estimate of between $25,000 and $51,000—while the watchmaker originally priced it at $90,000 in 2012—it sold for the impressive sum of $293,000 ! A remarkable achievement for this lesser-known watchmaker who is highly appreciated by enthusiasts of Japanese horology !

Masahiro Kikuno SO

The second piece he offered for the auction is very different from the first. Unlike his usual approach, Masahiro this time based the watch on a Seiko NH34 caliber and, for the first time, used a CNC machine to assist in the creation of the sky chart module and the dial. But why shift from traditional handcrafting to CNC machining you might ask? Simply because Masahiro now teaches at the Tokyo Watchmaking School and wanted to teach his students how to work with a CNC machine. He created one watch for himself, easy to wear on a daily basis, and a second for the auction. However, he made it clear that he does not intend to continue producing such pieces, as he naturally prefers handcrafting, longer and more difficult but ultimately more beautiful.

This watch, estimated between $640 and €2,300, ultimately sold for... $111,000!!!

It's astonishing, considering it’s based on a simple Seiko movement and a CNC-crafted module, but it reflects the status Masahiro Kikuno has achieved over the years. I can only be thrilled for him !

These results achieved by the young watchmaker from Hokkaido hint at a bright future for him and genuine recognition from the watchmaking community for his extraordinary work!

Masa’s Pastime

I will conclude with perhaps the least known independent watchmaker in our regions, but one of remarkable talent : Masa Nakajima.

I won’t elaborate too much on the topic, as I had the pleasure of meeting him during my last trip to Tokyo and am preparing an article on the subject, which will appear in the first issue of Wadokei Magazine !

Masa transitioned from being a professional diver to an antique dealer and then to a watchmaker—a rather unconventional journey ! His shop, located in the Kichijōji neighbourhood of Tokyo, has grown by offering watchmaking services, selling pocket watches, and even transforming pocket watch movements into wristwatches, all done in-house. Recently, he also began producing in-house movements and watches under his own brand, Masa & Co. And as you might guess, the “& Co” refers to an entire team of watchmakers, decorators, and engravers who work alongside him daily !

Masa’s Pastime répétition minutes

The first watch offered is another piece from Mark Cho's collection, the man in the shadows of this Phillips auction. It was a custom order he placed with his friend from Kichijōji to encase a 19th century minute repeater movement by A. Golay-Leresche & Fils, complete with it’s original enamel dial, in a wristwatch case.

As Masa is now focusing on his new brand, it is no longer possible to request wristwatch customizations based on pocket watch movements. So this was the last opportunity for anyone to see such a project through with Masa and his team. Indeed, the watch is currently fitted with a prototype case rather than the final white gold case that Mark Cho had envisioned.

That didn’t stop the watch from reaching a price of $49,000, a more than respectable result for this unique piece, which the lucky owner will be able to further personalize in the fabulous Kichijōji workshop! A very promising start for Masa and his team !

Masa&Co Nayuta Model A - TOKI

Among Masa's brilliant team is the young watchmaker Nayuta Shinohara, winner of the prestigious Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Award in 2020.

Masa decided to show the trust he places in Nayuta by giving him complete freedom to create a model of his choice to inaugurate the Masa & Co. brand.

Nayuta Shinohara

Credit: masaspastime.com

This led to the release of the Nayuta model in 2023, named after its designer, as the result of the collaborative work of young Shinohara-san and his colleagues in the workshop.

The model offered at the auction features their beautiful in-house movement and the design of the Nayuta A model, but with a stunning dial hand-engraved by the workshop's engraver.

Once again, I won’t go into further detail here, as the article planned for the first issue of Wadokei Magazine will cover the topic in depth !

I was delighted to see the success of this piece, which sold for nearly $72,000—significantly more than the $45,000 price of the base model offered by the brand. A fantastic result for this young brand, which deserves recognition and will undoubtedly gain increasing attention in the future !

Conclusion

We can see that the results for independents are far more satisfying than those for the major brands, confirming a trend that has been established for several years now. Buying a watch from an independent means acquiring a piece of craftsmanship, but also a fragment of the watchmaker’s soul. The approach that leads someone to independent watchmaking is entirely different from that of going for an established brand. A much deeper personal connection is created with an independent watchmaker, not only because things are often much more transparent, but also because it’s not just a transaction, it’s an encounter. I believe this is, in large part, what explains the success of independent watchmakers today.

Nayuta Shinohara, Masahiro Kikuno, Naoya Hida, Masa Nakajima, Mark Cho

Credit: Homer Narvaez for Tokyo Watch Club https://tokyowatchclub.jp/

I am truly delighted to see that this very important auction in the history of Japanese watchmaking has allowed the world to discover or rediscover names and faces that I hope will become familiar to enthusiasts. Beyond the watches themselves, getting to know the people who create them remains, in my view, one of the most rewarding aspects of the watchmaking passion and I look forward to introducing you, in the months and years to come, to all these artists and artisans who are breathing new life into Japanese horology !

I would like to sincerely congratulate these exceptional individuals who had the opportunity to showcase their talents to the watchmaking community. A round of applause as well to Mark Cho, who worked behind the scenes to bring these people into the spotlight ! They truly deserve all this success, and even more!

皆さんお疲れさまでした !!

Taro Tanaka beyond Grand Seiko

Taro Tanaka's name is almost always associated with Grand Seiko, but his career includes many other great feats that make him one of the most important people in Seiko's history. Unfortunately, these feats are too often ignored, and the impact that Taro Tanaka had on the brand's evolution is still underestimated. That's about to change with this article!

Vintage Seiko and Grand Seiko enthusiasts are mostly familiar with this name: Taro Tanaka.

Hired in 1959 by K Hattori (later Seiko Watch Corporation), he was the first industrial designer to join the company's ranks. His name is intimately linked with Grand Seiko, since it was he who drew up the rules of the famous “Design Grammar” or “Seiko style”, the set of aesthetic principles that gave the brand its visual identity.

But Taro Tanaka is a great misunderstood. Indeed, to reduce his work to Grand Seiko is a big mistake. I'd also add that the “Grammar of Design” itself is often misunderstood, even though it's the thing he's best known for.

The impact Taro Tanaka has had on Seiko as a whole is absolutely immense, and it's safe to say that Seiko wouldn't be where they are today without him.

So pour yourself a glass of your favorite beverage, get out your best tweed jacket and adjust your moustache, today we're going to walk in the footsteps of the great Taro Tanaka! And we'll also take the opportunity to debunk a few preconceived ideas in the process.

Credit Image: The Seiko Book

As we saw a short while ago, Taro Tanaka benefited from an exceptional mentor in the person of Ren Tanaka (they share the country's most used surname so I won't call them by their first names, sorry).

Ren Tanaka has always been Taro Tanaka's direct superior and has had a major influence on his career, from start to finish. While his mentor gave Seiko its corporate image (logo, official colors, standardization of image), Taro Tanaka, as we shall see, gave the watches a visual identity. Between them, they literally changed the face of Seiko from 1960 onwards.

I think it's important to go back over Taro Tanaka's career in a few points.

I'd like to make it clear that it's not possible to go into detail on every subject in a single article, so today you'll have to make do with an overview to try and highlight Taro Tanaka's importance beyond Grand Seiko.

1959, young Taro Tanaka, a recent graduate of the Chiba School of Engineering in Industrial Design, joins K Hattori.

Myth number 1: Taro Tanaka was an employee of Suwa Seikosha

It's not true. I don't know where this false information comes from, but it's not true. Taro Tanaka headed the design department of what was to become Seiko Watch Corporation, working with both Suwa and Daini. He would issue directives to both factories, and they would propose movements or ideas. Hierarchically, Taro Tanaka was at the top of the pyramid as far as design was concerned. He worked at the group's headquarters in Ginza. It was this location that prompted him to join Seiko.

Seiko Watch Corporation headquarters in Ginza today - Credit Anthony Kable www.plus9time.com

In 1960, after settling in and discovering the different workings of the company, the young Tanaka found himself faced with two problems. The first was that he was required to draw inspiration from Swiss watches when designing timepieces, which clearly restricted the designers' creativity. The second is more complex. In those days, designers weren't allowed to do as they pleased, but had to use specific measurements for the watch case, dial and glass, based on a chart from which they couldn't deviate. But since that's not enough, they also use a unit of measurement inherited from the french Ancient Empire: the line. A line corresponds to a twelfth of an inch, the equivalent of 2.2558 mm. The smallest unit is the quarter line, or 0.564mm. And to top it all off, these dimensions are then rounded, which makes the task very complicated, especially as drawings, prototypes and final products are all at different size scales, giving rise to real headaches between line/mm conversion and rounded figures manipulated in all directions.

The chart used by Seiko designers before Taro Tanaka

Credit: The Horological International Correspondance nº427 - 1995

But the problems with the line system don't stop there. Most of the subcontractors who made the cases and dials had switched to the metric system and worked to a tolerance of around 0.05mm, ten times more accurate than the smallest division of a line.

Between random measurements and the difference in tolerance between the design and the concept, the manufacture of exterior parts is therefore not very precise, leading to a lot of wasted material during manufacture and a very approximate fit between parts. The direct consequences are obvious: it's very difficult to make modern, high-quality products in large numbers that are truly watertight and durable (especially in a country as humid as Japan).

There are many other problems with this system, but I won't go into too much detail, since you've already got the general idea: the line and the design standards used are hellish.

Only two years after his arrival, Taro Tanaka revolutionized Seiko's approach to design by creating a new standard that would replace the old table imposed on designers and abandon the line. He got together with designers from K Hattori, Suwa Seikosha and Daini Seikosha - no more than 10 people in all - and developed this new millimetric standard, in agreement and collaboration with their subcontractors.

This new way of conceiving watches adopted in 1961 would fundamentally change the way things worked, and from a design point of view, Seiko would enter a new era, with much more modern designs and cases, and improved water-resistance. This new approach also laid the foundations for what was to become the “Grammar of Design”, but we'll come back to that later, first things first.

The first project that Taro Tanaka will be able to tackle with his new standard is proposed and directed by Ren Tanaka. The idea is to create a range of quality watches, mass-produced for the international market and targeted at young people. These watches will have everything to please them: water-resistance, automatic winding, day and date, a sporty but not extreme look, a watch that can be worn in all circumstances, at the beach, for sport, in the shower, at work. In short, absolutely everything you could ask for in a modern watch, and a little more. For its time, it's a high-quality, innovative product. But what's more, it will be offered at a very affordable price, since we're targeting young people here. And of course, it's Taro Tanaka who will be in charge of the design for this project, named by Ren Tanaka “Sportsmatic Five”, a project that would never have been possible without the new design standard imposed by Taro Tanaka.

Credit: Anthony Kable www.plus9time.com

The young designer had the revolutionary idea of placing the day and date in a single window at 3 o'clock. At the time, this complication was not commonplace, and the day of the week was usually shown in full in a window at 6 or 12 o'clock, like Rolex's famous Day Date (released only a few years earlier) for example. But in the '50s, Seiko's engineers worked hard to develop watches where information was grouped together: hours, minutes and seconds were displayed by hands all located in the center of the dial. You can read the time at a glance, in a much more ergonomic way. For Taro Tanaka, the same should apply to the day and date. This detail, quite important at the time, would become one of the brand's hallmarks.

The Sportsmatic 5 ref 41897 de 1963

Another feature of the Sportsmatic Five is the recessed crown at 4 o'clock, hidden to emphasize the efficiency of the automatic Magic Lever system introduced in 1958. Already used in the Seikomatic range, this feature would also become one of Seiko's symbols.

The first Sportsmatic 5 from 1963 was the first watch in the world to win the Good Design Award.

The Five range was an immediate worldwide success (thanks, among other things, to the Tokyo Olympics in '64), becoming a symbol in its own right for Seiko, with several tens of millions of watches produced over almost 60 years. They also played a decisive role in the boom in Japanese watchmaking in the '60s and in the Swiss watch crisis of the '70s and '80s, far more so than quartz! Another misconception to forget: it wasn't quartz that caused the Swiss watch crisis, but that's not today's topic...

One last point about the Seiko Five: according to Taro Tanaka himself, the 41897 from 1963 remains his most successful design to this day.

Myth 2: Taro Tanaka = Grand Seiko

As I said in my introduction, Taro Tanaka is too often summed up by his involvement in the design of the Grand Seiko, but he had other incredible achievements that helped give Seiko its image, as can be seen throughout this article.

But it's true that we can't talk about Taro Tanaka without mentioning the famous “Grammar of Design”...

Myth 3: Its real name is not grammar of design, but “Seiko style”.

The idea was born in Taro Tanaka's mind in 1962, when he compared Swiss watch production with the Seiko watches offered in Wako. A year earlier, he had developed Seiko's new design standard, which allowed for greater creativity and evolution in terms of design, but the brand was struggling to find its feet and the comparison with the Swiss was as inevitable as ever. He therefore decided to take the process a step further and draw up a set of specifications to give Seiko a style all its own and ensure the commercial success of these watches.

It's important to remember that in 1962, Grand Seiko was not a brand or a range, but a single model, Seiko's top-of-the-range model. So when Taro Tanaka began to look into the matter, his aim was to implement an aesthetic language specific to Seiko as a whole, hence the name “Seiko Style” (pronounced in English even in Japanese).

Myth 3bis: Design Grammar is unique to GS and KS...but...

Contrary to what you might think, the Seiko Style is not specific to Grand Seiko or King Seiko, since it is designed to give a visual identity and attract customers to the brand as a whole. But...but but but...one of the key features of Seiko Style is the use of perfectly flat surfaces, polished so as to be distortion-free - the famous Zaratsu. However, this kind of work requires real expertise and a great deal of time on the part of highly-skilled craftsmen, which is reflected in the watch's final price. These features are only fully exploited on the top-of-the-range King Seiko and Grand Seiko watches. This is not to say that the Seiko Style was not used to a lesser extent on the rest of the production line - quite the contrary. In fact, Seiko Style is a global philosophy, with different “currents” or applications, the most complete of which can be found in Grand Seiko watches from the 44GS upwards.

So, as we've just seen, the idea of the Seiko Style originated in Taro Tanaka's head in 1962. It's a common misconception that the idea came to him as an epiphany, one day while strolling along Tokyo's Champs Elysées, but this is not exactly the case.

Taro Tanaka uses a very specific expression when telling this story. He says that with the drab design of Seiko at the time, it was impossible to “surpass Switzerland”. In fact, these were not his words, but those of Shoji Hattori, president of the group since 1946, whose motto was “Catch up with and surpass Switzerland” (an expression taken up by Pierre-Yves Donzé for his fabulous book of the same name).

It's this idea of surpassing Switzerland that has driven the company for some years now, and which will be the driving force behind all its successes in the years to come. But in the meantime, Taro Tanaka is working to create a visual language that will enable Seiko to go beyond Switzerland and give its watches a recognizable, luxurious image.

Without going back over the various rules laid down by Taro Tanaka, the rest of the story is clear: the first watch to perfectly embody these rules is unanimously the 44GS, released...5 years later!

So it's fair to wonder what went on for 5 years! Especially when you look at the number of watches released between 1962 and 1967, you have every right to wonder to what extent the Seiko Style influenced them, or even if the 44GS really was the first watch to bear the “Grammar of Design” stamp.

Let's take the example of the second Grand Seiko released in 1963, the 57GSS. This was the first watch to benefit in part from the famous zaratsu polishing, and it shows some of the beginnings of the Seiko Style with its flat dial, double hour markers at 12 o'clock, bevelled hands and so on. But it doesn't tick all the boxes either, with lots of rounded and curved surfaces, its crown not integrated into the case, no inverted inclinations for the mid-part of the case etc. We can also think of King Seiko models such as the King Seiko Calendar (4402) or the Chronometer (4420), which hint at the gradual evolution of design at Seiko under the leadership of Taro Tanaka.

44KS Chronometer

Credit: Ikigai Watches

57GSS “Toshiba Special”

Credit: Ikigai Watches

It seems clear to me that during these 5 years of development, Taro Tanaka perfected what would become the famous “Grammar of Design” as we like to call it, fine-tuning certain rules (the flat dial dates from the new design standard in 1961) and gradually incorporating certain details into different watches, before culminating in the one that would be the most perfect expression, the famous 44GS from Daini Seikosha.

So I think we should see the Seiko Style not as an absolute truth established in 1962 and used in 1967, but as an idea that made its way into the mind of its creator to evolve and mature to its finest expression in Daini's masterpiece, the 44GS.

Taro Tanaka was a refined and elegant man, and this image fits perfectly with the image one might have of Grand Seiko. But he didn't just make dress watches, far from it! He also left his mark on Seiko's history with the Five range, as we've seen, but also with sports and professional watches.

He was responsible for the design of the numerous stop-watches released by Seiko for the 1964 Olympic Games, as well as their development for the 1972 Sapporo Winter Games. It's hard to imagine a more sporting pedigree for a watch than participation in two Olympic Games!

Updated model for the 72 Sapporo Winter Games

Credit: Seiko Museum

He was also behind a number of diver watches.

Seiko 6215 and 6159 300m

Credit: vintagewatchco.com

He designed Seiko's very first professional divers, the 6215 and the 6159-7000 the following year. He then spent 7 years working on the ultimate watch for professional divers, following a letter of complaint written by Hiroshi Oshima in 1968, a diver with the Japan Marine Industry Company, whose 6159-7000 had simply exploded when his capsule decompressed.

Taro Tanaka worked closely with divers in Hiroshima's Kure harbor (also known as Japan's largest naval base and home to the Yamato) to develop a watch that met all their needs. The young engineer Ikuo Tokunaga, freshly graduated from the prestigious Waseda University in 1970, worked on the project, but the paternity of the watch, its design and all the work done in collaboration with the Japan Marine Industry teams from 1968 onwards belong to Taro Tanaka.

In 1975, the legendary 6159-7010 Grandfather Tuna was released, considered to be the world's finest diver's watch. For this watch, Tanaka worked with Nemoto Special Chemical, a Japanese company specializing in luminous paints since 1941, to develop a luminous material. Instead of tritium and other radioactive luminous materials then commonly used in watchmaking, his aim was to create a non-radioactive luminous paint for the Hiroshima divers. This exclusive paint for the Grandfather Tuna, called “NW Luminous”, was the world's first non-radioactive white luminous paint, a real innovation in watchmaking history, and the forerunner of Seiko's famous Lumi Brite. In 1993, Nemoto sold the “Luminova” license to the Swiss, while Lumi Brite remained a separate product, patented by Seiko.

But although this watch featured an impressive number of innovations, patents and world firsts, it was replaced 3 years later, in 1978, by an even more advanced version, this time equipped with a quartz movement: the no less legendary 7549-7000 Golden Tuna.

This next step in the global history of diving watches (the world's first quartz diver) will also be the very last watch designed by Taro Tanaka. Indeed, when Shoji Hattori died on July 29, 1974, a promising young Seiko executive decided there was no need for a design office, and it was dissolved in 1974, leaving Daini and Suwa in charge of all watch design matters, without an authority to oversee this heavy task and issue directives, as Taro Tanaka had done since 1959.

Ironically enough, when Suwa intended to release the Golden Tuna after the dissolution of the design studio, no designer was in a position to design such a watch, so they had to call on Taro Tanaka as product manager.

I don't know about you, but for me the Golden Tuna just took on a whole new dimension!

So you must be wondering what became of Taro Tanaka after the dissolution of the design studio of K Hattori (future Seiko Watch Corp).

Well, once again, he remained under the guidance of his lifelong mentor, Ren Tanaka, who established K Hattori's Customer Service Department in February 1976. Taro Tanaka was its manager, as well as responsible for catalog production, until the end of his career.

Years later, Seiko Watch Corp. re-created its design studio in Tokyo, realizing the serious mistake made in 1974, but this time without Taro Tanaka, who had already retired. Until recently, the studio was run by the talented Nobuhiro Kosugi, now retired.

Taro Tanaka's career as a designer only lasted about fifteen years, but he brought Seiko into the modern era and was a decisive player in the race Seiko won against Switzerland. He put his talent at the service of a global policy launched by Shoji Hattori, son of Kintaro Hattori, and gave a face to Seiko, creating popular watches like the Five, luxurious watches like the Grand Seiko, divers like the 6105 or the 6159 300m, sports watches like the 64 and 72 Olympic stopwatches, and special watches like the Tuna 600m, for which he was the mastermind of what would become the Lumi Brite and the Swiss Luminova.

In addition to the watches themselves, he developed the xxxx-xxxx format reference system that is still in use today, and also helped Seiko to structure itself internally with catalogs, at a time when Seiko kept almost no track of the inventory and sales results of each of its references.

In my opinion, Taro Tanaka remains one of the greatest names in the history of Seiko and watchmaking in general, and I hope this summary has helped you better appreciate the monumental impact he has had beyond Grand Seiko.

Taro Tanaka's mysterious mentor

Taro Tanaka is a familiar name to Seiko enthusiasts, but the story of his mentor has never been told before. I'd like to introduce you to this important but little-known figure, who also had a profound impact on Seiko's development, anonymously... right up to the present day.

One of the most famous names in Seiko history is Taro Tanaka. A legendary designer, he played a major role in Seiko's evolution and was the driving force behind Seiko's global success in the late 60's and 70's, being the first industrial design graduate hired by Seiko in 1959.

But Taro Tanaka also had a mentor, 10 years his senior in the company and product manager since 1950, who also had a major influence on Seiko throughout his career, from 1949 to the late 80s. His name was Ren Tanaka.

Credit: The Horological International Correspondance

The name probably means nothing to you, yet his impact was at least as great as that of Taro Tanaka.

I first became aware of this key player through an interview with Taro Tanaka published in the book “The History of Seiko 5 Sports Speed-Timer” by Sadao Ryugo, but the Internet was absolutely silent on the subject. In the end, to my knowledge, the only information on this Seiko monument can be found in The Horological International Correspondance.

So today, I invite you to discover the greatest achievements of Taro Tanaka's mentor.

In the early 50s, Ren Tanaka developed and named the TimeGrapher, a tool familiar to watchmakers the world over. At the time, the Swiss used an equivalent tool called the Vibrographe. Ren Tanaka's machine was a great international success, becoming one of the most important tools for any watchmaker to this day.

Just one year after joining K Hattori (now Seiko Group), Ren Tanaka became product manager, overseeing Daini and Suwa production in the decisive decade that gave rise to the still-present rivalry between these two companies, a rivalry in which he played an important role. Importantly, it was he who came up with the names King Seiko and Grand Seiko, essential symbols of this fraternal rivalry.

Credit Seiko Museum

Credit Seiko Museum

60 years on, its legacy is still relevant, since as you know, Grand Seiko is celebrated its 60th anniversary a few years ago and King Seiko is having a come-back, with the launch of the KS1969 a few days ago.

In 1961, he marketed a product that may seem anecdotal, but which in the end represented the visionary side of its creator: Disney Time.

At the time, watches were overwhelmingly reserved for adults, but Ren Tanaka had the idea of “planting the seed” of Seiko in the minds of younger children by making watches for them. So he targeted children aged 4 or 5, visiting schools to better understand their tastes. He then traveled to Los Angeles to meet Roy Disney, Walt Disney's brother and President of Walt Disney Productions, to negotiate the use of the name and the most iconic Disney characters.

Roy Disney - Credit chroniquedisney.fr

When color TV made its appearance in Japan in 1960, people were struck by the bright colors. So Ren Tanaka's priority was to achieve the same color rendering on the watch dials, which still had to be very affordable. The first generation of Disney Time watches were equipped with paper dials.

Credit Seiko Museum

The watches were marketed in 1961, with a lot of work done on the packaging to appeal to children, at a price of ¥1950 (equivalent to less than US$30 today). They were an immediate success in playgrounds, and the Disney Time range continued into the 1980s.

Credit: The Horological International Correspondance

This example, which may seem insignificant at first glance, clearly shows that Ren Tanaka is a product manager with a vision, someone who can think outside the box to propose very interesting watches and make real advances in marketing.

But one of Ren Tanaka's most memorable achievements was surely designing the Seiko logo in the late '50s. It was he who created the brand's mythical typography, still used today on the billions of dials produced over the past 60 years by the Tokyo-based firm, and on all their communications. The brand's visual identity was virtually non-existent at the time, and it was when he saw the American Airline's that he decided to create a logo for Seiko. It was also he who, with Shoji Hattori's approval, chose the brand's signature blue for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, thus completing Seiko's visual identity.

The Seiko logo and color are, according to Ren Tanaka himself, two of his three greatest successes. The third, and by no means least, is the creation of the Seiko 5.

It's important to understand that in those days, Seiko operated very differently from today. The idea was to say “how can we sell what we make”, which explains why the sales department was hierarchically above the product planning department, to the extent that a sales manager could decide whether or not a product appeared in the catalog without informing the designers or product managers. But Ren Tanaka decided to completely change the company's mindset by reversing things: it was now necessary to design products that sell, and therefore to put the emphasis on marketing. He developed a passion for marketing and began to study it by immersing himself in Western books, since marketing was not a highly developed discipline in Japan at the time.

This was the inspiration for the Seiko Five, launched in 1963.

Credit: www.plus9time.com

The design was entrusted to Taro Tanaka and “the rest is history” as we say. The success was incredible, giving birth to a range of watches that was absolutely emblematic for Seiko, and was one of the essential determinants of Seiko's success in the 60s and 70s.

Just as with Grand Seiko, just as with the brand's visual identity, its heritage has continued to this day, with the Seiko 5 Sports range renewed a few years ago and being an huge global success.

One of the other key events in Seiko's history in the 60s was their participation in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics as official timekeepers, a story partly told in the article “How Seiko entered the exclusive club of sports chronometry”.

The manufacture of large clocks was the responsibility of Seikosha Clock Factory, chronographs and time-measuring instruments for swimming were made by Daini Seikosha, the famous Crystal Chronometer quartz chronographs are manufactured by Suwa and the three factories shared the production of printer chronographs. And, as you've already guessed, the conductor behind the scenes directing all this effort to bring sports timekeeping into a new era was none other than Ren Tanaka.

Credit www.plus9time.com

His experience in directing such projects led him to head the team in charge of products for the Osaka International Exhibition in 1970. He also led the Suwa and Daini teams in the development of chronometry solutions for the Sapporo Winter Games in 1972, two important events in Seiko's history, cementing their success in the 1960s in the wake of quartz's historic turnaround.

Credit: www.plus9time.com

His visionary nature, excellent leadership and many qualities as a product manager convinced Seiko CEO Shoji Hattori to entrust him with increasingly important projects for the group.

In 1976, Ren Tanaka organized the development of the Customer Service Department, whose importance he emphasized by insisting that after-sales service should also be seen as pre-sales service, consolidating a brand's reputation and reassuring the customer - further proof, if any were needed, of his understanding of the market and marketing.

Focusing on the individual is not part of Japanese culture, and I think this explains why, even today, many of the names of the men and women who shaped Seiko's history remain unknown to the general public. I was stunned to discover the astounding silence surrounding such an important person as Ren Tanaka. It's a privilege to be able to put this name in the spotlight so that he can be recognized for his innovations and the indelible mark he has left on Seiko's history.

Duel at the North Pole : Seiko VS Rolex

Naomi Uemura is a great Japanese explorer, but one of his adventures at the North Pole was an unintentional opportunity to face Seiko and Rolex in the most extreme conditions imaginable! Here's a look back at an extraordinary expedition that blends human adventure and watchmaking.

Among Seiko's emblematic divers, we find the 6105-8110 aka Apocalypse Now or Captain Willard here, but nicknamed the Naomi Uemura in Japan.

Although it is found on Martin Sheen's wrist in FF Copola's film since it equipped many American soldiers in Vietnam, in Japan it is better known for having long accompanied one of the greatest Japanese explorers, Naomi Uemura.

Uemura was known for his solo feats. Before he turned 30, he had climbed Kilimanjaro, Mont Blanc, the Matterhorn and Aconcagua solo. In 1970, he was part of the first Japanese expedition to the summit of Everest. He also traveled the 6,000km of the Amazon alone on a raft. But he is best known for being the first person to reach the North Pole solo in 1978. For his expedition to the top of the world in 1970, he wore a Seiko 6159 -7000 released in 1968 with its one-piece case and its Hi Beat caliber adjusted to Grand Seiko standards.

He then crossed the Great Canadian North with his sled dogs in 1975 and 1976, which gave him some notable experiences. One morning, he heard a bear rummaging through his belongings and eating some of his food. The next morning, Uemura was ready and he shot the predator point-blank in the head. Later, he found himself stranded and adrift with his sled and his dogs on a piece of ice that had separated from the pack ice. After an interminable wait, a small ice bridge less than a meter wide reformed and allowed him and his dogs to continue their journey more serenely. Following his exploits, he received the Explorer Award in 1976 and Rolex Japan gave him an Explorer II.

Taken from a book about Naomi Uemura, here’s his 1655

This is when things get interesting

He left for the North Pole in 1978 with his Rolex on his wrist. But the polar temperatures (literally) made him fear frostbite where the watch that he wears on its steel bracelet touches his wrist. He therefore puts it on a leather strap but the watch cannot withstand the very strong vibrations linked to his travels in a sled dog and the leather does not take long to give way. He finds no other solution than to wear the watch on his waist but without the warmth of his wrist and in extreme temperatures, the oils in the movement freeze and the watch stops.

During a supply stop, he meets Mr. Sugawara from the weekly Bunshun who follows his journey and brings him supplies. Sugawara offers Uemura to exchange his Rolex which stopped running for his own Seiko 6105...

Credit Fratello Watches

Sugawara leaves with the Rolex and he will later say that once it had returned to temperature, the watch had started working again without problems.

Credit Fratello Watches

For his part, Uemura Naomi continues his journey across the Far North.

And on his wrist, Sugawara's 6105. On a very cold day, the watch will stop momentarily, but the fact that it is worn on a rubber strap greatly reduces the risk of frostbite and allows it to be worn until the end of this incredible journey.

When he returned to Japan, Sugawara offered to return his Rolex to Uemura, but Uemura offered it to Sugawara and he ultimately kept the 6105 on his wrist for many more years.

Uemura sadly lost his life in 1984 while descending Mount McKinley.

The subject of frostbite will remain at the heart of Seiko's concerns for this type of watch and a few years later, during the development of different Landmaster models for other explorers or in honor of Uemura, Seiko will use special coatings and titanium to avoid any risk of frostbite when the watch is worn directly on the skin in extreme conditions.

These watches also all use the GMT function, like the Explorer II from Uemura.

Naomi Uemura also appears in a Rolex ad for her GMT Master, probably before the '78 expedition.

After hearing this story, the last words of this ad sound a little bit ironic.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not trying to start yet another stupid Rolex vs. XXX keyboard war, but the story and the vagaries of Uemura's polar adventures have allowed Seiko to win a beautiful duel against the king of explorers watches, the famous Rolex Explorer II.

This is one of the many adventures in the beautiful history of Seiko and its many little-known feats. But the 6105 is surely the Seiko diver that has had the most extraordinary stories on the wrists of explorers, American soldiers and other adventurers of the late 20th century. And it’s a real honor for Seiko to have managed to beat the legendary Rolex Explorer on its own turf!

Seiko released a reissue of legendary divers last year with the SLA033 which very faithfully reproduces the 6105-8110. And in 2020, they released a modernized and more affordable version with the SPB151 and 153.

Credit Fratello Watches

For me details about the fascinating life of Naomi Uemura, here’s an interesting link. There’s also a Museum in Itabashi, Tokyo, completely dedicated to him.

Fisticuffs in Bangkok: Seiko VS Omega

The history of confrontations between the Japanese and Swiss watchmaking industries is fascinating, and I'd like to introduce you to a first part , with the fierce battle between Omega and Seiko after the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games, over the Bangkok Asian Games.

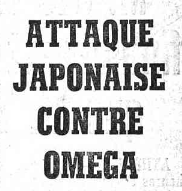

No, we're no longer in the middle of the Pacific War, but on August 14, 1965, and the Gazette de Lausanne has a rather warlike headline.

Building on its brilliant success at the Tokyo Olympic Games in October 1964, Seiko became a world-class sports timekeeper in less than five years, its revolutionary products for the time enabling it to win this prestigious contract from its Swiss rivals, headed by Biel-based Omega. Following the success of the Olympic Games, Seiko submitted its application to be timekeeper for the 1966 Asian Games, the fifth edition of which was to be held in Bangkok in December of that year.

In addition to the chronometry solutions, Seiko is offering to provide three giant electronic scoreboards worth 250,000 Swiss francs free of charge, with the total cost of the installations amounting to 500,000 CHF.

The Bangkok preparatory committee was not indifferent to Seiko's proposal, which came at the end of 1964, after the Tokyo Games. But as revealed by the Gazette de Lausanne, Omega signed an exclusivity contract with the committee on April 27, 1964.

“We have developed a piece of equipment that is superior in many respects to the one our company used for the Tokyo Olympics. We would be happy to use it for an international event.” These are the words of a Seiko spokesman reported in this article of August 14, 1965.

With a tempting proposal from Seiko, which had just beaten Omega to the timing contract for the Tokyo Games, and a contract signed with Omega before the '64 Olympics and Seiko's success in this venture, the Thai committee set up a sub-committee to find a compromise.

But Omega refused from the outset to share the event with Seiko, considering that this solution “would represent a definite loss of prestige in Far Eastern markets”, and proposed other solutions to the committee, with the support of the Fédération Horlogère.

Five days later, on August 19, 1965, the Gazette de Lausanne and the Journal de Genève both published an article explaining that Omega had also submitted its bid for the 1968 Mexico Games as early as April 64, at the same time as its bid for Bangkok, whereas Seiko only did so at the end of 64, after the success of the Tokyo Olympics and at the same time as their application for Bangkok.

A few days later, Omega learned that the organizing committee for the Mexico Games had decided to entrust Omega with the timing of their events.

Omega archives - Credit Fratello Watches

It is in this tense context that the Fédération Horlogère Suisse is getting its message across through the two most important newspapers in French-speaking Switzerland:

« According to the Fédération Horlogère Suisse, the decision taken in favor of the watchmaking industry by the Mexican organizing committee is all the more gratifying in that it puts the awarding of sports timekeeping in an objective perspective, i.e. based on purely technical criteria and on the quality of the services offered to the exclusion of all other considerations (unlike what happened at the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games, where the awarding of sports timekeeping was not subject to proper competitive bidding).

According to the Fédération Horlogère, the awarding of the timing of the Mexico Olympic Games to the Swiss watchmaking industry, following similar decisions taken for international sporting events in Brazzaville, Winnipeg, Kingston, Kuala-Lumpur and Montreal, confirms the supremacy acquired by the Swiss watchmaking industry in the field of sports timing and short time measurement. »

That's how this article against Seiko concludes, in an already electric context, which sounds as much like a frontal and unjustified attack on Seiko as an attempt to reassure itself about alleged Swiss supremacy.

It's worth pointing out that the comments made by the Fédération Horlogère at the time were completely untrue, since, as explained in the article “How Seiko entered the exclusive club of sports timing”, it was Seiko's technical superiority that allowed them to be the official timer of the Tokyo 1964 contract.

A horological conflict about the 1966 Asian Games. Thailand gives preference to Seiko after signing a contract with Omega

On August 30, 1965, L'impartial, a La Chaux-de-Fonds newspaper, devoted a detailed article to the situation, telling us that the story had turned into a diplomatic affair, as the Thai ambassador to Switzerland was summoned to the Federal Political Department after the Thai Foreign Minister had announced that he wished to give preference to Seiko for the Asian Games. A few days later, it was the Swiss ambassador in Bangkok who was received by the Minister of Foreign Affairs to present the contract signed by Omega and inform him that, if necessary, Switzerland would not hesitate to appeal to an international arbitration tribunal.

However, the organizers of the 5th Asian Games made their decision and “finally accepted the Japanese company's offers, which were far more advantageous”, as the article points out.

Watchmaking competition between Switzerland and Japan: who will win the Asian market?

After the Fédération Horlogère, this time it's Omega's turn to address its message directly in this article, arguing that Seiko obtained this contract thanks to its economic influence in South-East Asia, and denouncing “Japanese dumping methods” as the reason for bringing an international arbitration case into play.

The article concludes by criticizing the so-called “dubious Japanese methods”, whereas it opened with a more advantageous Japanese offer.

Swiss watchmaking to take new measures to counter japanese competition

Despite the various invectives and threats, another article in L'Impartial published in December 1965 on the watchmaking battle between Switzerland and Japan in Asia confirms that Omega did make counter-proposals, trying to match Seiko's offer, but with no success.

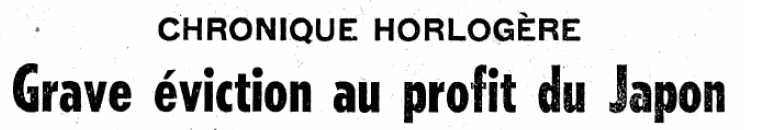

Then on March 4, 1966, the Gazette de Lausanne headlined in its economic and financial section, “Omega is deprived of timekeeping for the 5th Bangkok Games in favor of a Japanese watchmaking company”, while the Geneva newspaper reserved a small insert in its international politics page with the discreet title “Vème Jeux asiatiques de Bangkok, Le chronométrage unilatéralement retiré à une maison Suisse” (“Vth Asian Games in Bangkok, Timekeeping unilaterally withdrawn from a Swiss company”). In its watchmaking column, L'Impartial headlines “Grave éviction au profit du Japon” (Serious eviction in favor of Japan), while L'Express announces that “Timekeeping for the 5th Asian Games in Bangkok is unilaterally withdrawn from a Swiss company by the organizers”.

The articles explain that on March 2, 1966, the final decision to award the Asian Games to Seiko was taken by its organizers... following Omega's refusal to share timekeeping with Seiko!

So, despite Omega's counter-proposals and the proposal to share the event with Seiko, and despite threats of international arbitration, it will indeed be Seiko that will be in charge of deploying its technological innovations and timekeeping solutions for the 5th Asian Games, thanks to the more advantageous offer that had already been on the table several months earlier.

Everything is an excuse to justify Omega's reaction: Seiko is outbidding and dumping, they appeal to the “Olympic spirit”, they explain that the timing of international events is too complex to be shared, that sharing the event with Seiko offers Omega no “technical assurance”, they criticize Seiko for having embarrassed Thailand, and they even go so far as to say that technical, legal or fairness considerations were not taken into account by the organizers!

The blame is laid at the door of both Seiko and the organizers, but at no point is there any question of Omega and its inadequate counter-proposals, which clearly do not allow the Biel-based manufacturer to align itself with the Tokyo-based company's proposals.

M Rajamani, 400m womens

The Bangkok Games went off without a hitch, with two models of wristwatches sold especially for the occasion with the Games logo engraved on the case back, and many other derivative products. Seiko remained timekeeper of the Asian Games until 1994, and also timed dozens of other major international competitions.

Credit: Cedlamontre on montrespourtous.org

Credit: badaxjava on WatchUSeek

Credit : OLD MAN Secret vintage watches on Facebook

The conflict between Seiko and Omega in the late 60s is also another opportunity to see how the Swiss press dealt with Japanese watchmaking issues. Only articles written by people with first-hand experience of the Japanese watchmaking industry warn of the real threats posed by Japanese competition (as in the article “Has Swiss watchmaking lost a battle?”).

Beyond the deafening silence on Japanese innovations, the rest is made up almost entirely of articles that are at best disparaging, at worst untrue, about Seiko and Japanese industry. Another striking example of this biased media treatment is the alleged industrial espionage affair that saw Switzerland once again attempt to undermine Japanese industry in the early 70s, again without success... But that's a story for another day!

Here are extracts from Seiko's internal publications about the Bangkok Asian Games. Many thanks to Anthony Kable of Plus9Time for this valuable documentation!

Seiko Sales 11 and 12 from 1966 (slide for more)

Suwa Seikosha internal magazine, 1966

Suwa Seikosha internal magazine, 1967 (slide for more)

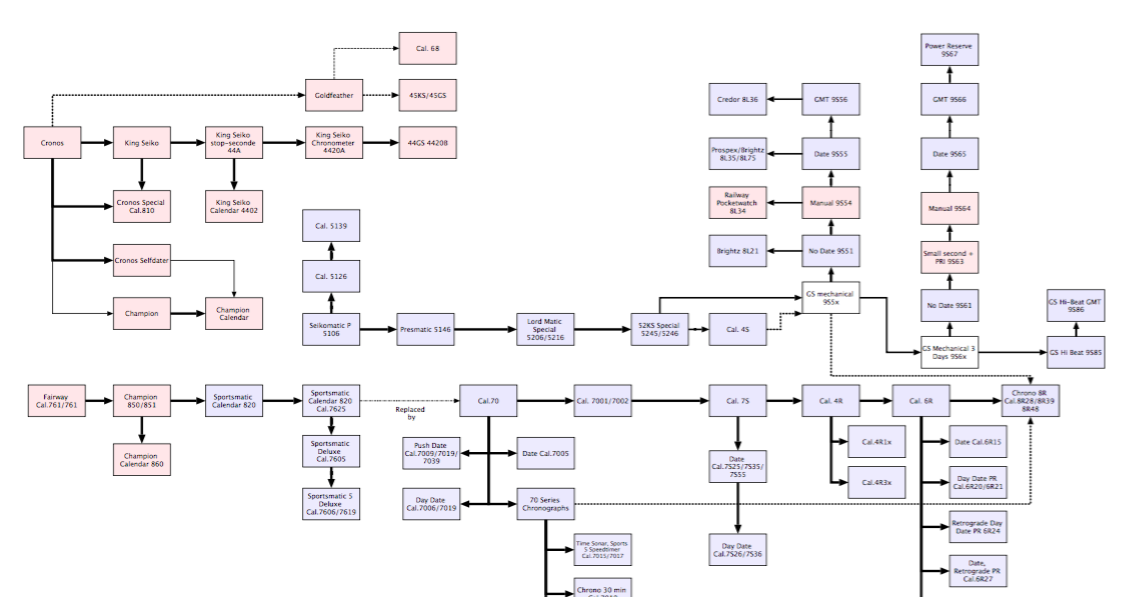

Seiko movements family tree

I present here a unique document, a “family tree” of the various mechanical movements for men developed by Seiko from the late 1950s to the present day.

The multitude of references in Seiko's history can be difficult to navigate. That's why I wanted to translate an excellent chart found in the book “Domestic Watch - Seiko Crown, Cronos, Marvel” by Yoshio Nagao & Yoshihiko Honda. This diagram is a sort of family tree of all Seiko's modern era manual-winding movements, from the 50s to the 70s.

After translating it, I thought it might be interesting to add a few automatic movements that were clearly the evolution of manual movements already present on the tree, so I might as well make the most of it. Then things escaladed quickly and I tried to make the tree as complete as possible, from the Marvel (1956) to the present day, concentrating solely on mechanical movements.

Of course, this work would never have been possible without the valuable information found in the book by Honda san and Nagao san, as well as in another book in the same series, “Domestic Watch - Seiko Automatic Updated Volume” by Mori Takeshi.

This diagram will need to be refined, corrected and completed, but this first version already covers almost every mechanical movement that has ever existed. Some movements, such as the 4S, have not been detailed in all existing versions.

One of the difficulties lies in the fact that Seiko changed its movement nomenclature in the early 60s from 3-digit to 4-digit. On the other hand, at that time, a movement corresponded to a particular range/name (e.g. cal.603 is exclusive to the Seikomatic), but over time, the same movement ended up in different ranges, and the same range may use several different types of movement. So you'll find both proper names (Marvel, Cronos, Skyliner etc) and movement references (cal. 6216, cal. 76 etc) or a mix of the two (Diver's 6105).

I hope that this huge amount of research, translation and formatting will be of use to the most ardent vintage enthusiasts, or at least help the curious to understand where certain modern movements come from.

Has Swiss watchmaking lost a battle?

This article from a Swiss newspaper from 1968 shows how advanced Seiko was back then and how the first signs of the big crisis the Swiss industry went through in the 70s.

Originally posted in March 25, 2020

« Ten years ago, competition from Japanese products was not taken seriously. Only a few well-informed producers were concerned, notably in the USA, Germany and Switzerland. But the public shrugged its shoulders. They “swallowed” all the “stories” told by retailers: the Japanese were copying, they weren’t inventing anything, their merchandise was of poor quality, and so on. Since then, however, faced with the commercial success of Japanese industry - whether in watchmaking, electronics, household appliances, machine tools or optics - public opinion has become aware of the Japanese challenge. Long lulled to sleep by gossip, the West is awakening, trembling. Yesterday unaware of the threat, it is now trying to ward it off. Here, we will examine just one aspect of the problem that is of particular interest to the Swiss: watchmaking. »

In the course of my research into Seiko, I came across this excellent article in the Journal de Genève, dated... June 19, 1968! And yet, reading this introduction, you wouldn't expect an article going back that far!

https://www.letempsarchives.ch/page/JDG_1968_06_19/9/article/8102630/seiko

Here’s a translation of the full article that follows the quote above:

For this study, we will base ourselves on the travel report in Asia by Dr Pierre Renggli, taken from a document presented to the ASUAG (future Swatch Group) Executive Committee.

Despite the dismantling of giant trusts, Japanese industry is very concentrated. The size of Japanese companies therefore far exceeds that of Swiss companies, which gives them, initially, an undeniable advantage. Furthermore, the State, without directly subsidizing the economy, exercises a positive influence by supporting, through its decisive action in the financial sector, the companies whose development chances are particularly interesting. In experience, this financial dependence of Japanese industry has proven favorable. In his report, Mr. Renggli notes: we should not speculate on the fact that the Japanese expansion drive would diminish, for the sole reason that companies in this country do not have surplus capital, like certain Swiss brands. Their economic expansion will not come up against financial problems, but rather the lack of labor qualified.

STRUCTURE OF JAPANESE WATCHMAKING

Image of this centralization, the production of wristwatches is essentially in the hands of four producers:

K. Hattori & Co.: 50% of production (number of pieces), brand: Seiko;

Citizen Watch Co.: more than 30% production;

Orient Watch Co. and Ricoh Watch Co. share the rest of the market.

Hattorl, which owns 45% of the capital of Orient Watch Co., is a powerful trust made up of several factories which employ 1,500 to 4,000 people. This company produces approximately 600,000 pieces per month (1966 figure), or approximately 10 to 12 times more than a medium-sized Swiss company. Citizen manufactures 370,000 pieces per month, Ricoh 120,000 and Orient 90,000. These four big Japanese brands are supported by numerous subcontractors, but it is the brand who launches the finished product on the market. In Switzerland, it is often the opposite, hence a certain disadvantage in terms of market penetration strength.

TECHNICALLY, THE EQUAL OF THE SWISS

From a technical point of view, the Japanese focused on anchor movements. They do not produce any Roskopf watches. Their production is characterized by very sophisticated goods. The standard (and cheap) product has little or no success with them. Automatic and shockproof watches represent 50% of production. 70% of the men's watches are equipped with calendars and 35% with the day-date system (day in full letters plus the date). Seiko and Citizen also manufacture electric watches and are actively studying quartz movements, as is Ebauches SA, which has just produced interesting protoypes. As for atomic clocks, Japan does not yet manufacture them. Japanese watchmaking has very little interest in specialties: extra-flat watches, diving watches, high-frequency watches, etc.

The myth of the standard, cheap Japanese watch must disappear. Today, Japan's policy is to adopt and implement, very quickly and on a large scale, immediately, the most progressive solutions. Moving towards Swiss watchmaking technology, the Japanese have, without a doubt, copied a lot of the Swiss industry. However, they are at the origin of technical novelties that can easily hold their own against Swiss counterpart. On this point Mr. Renggli is categorical: Today we must see them as a competitor who has reached our level in many areas.

AT THE FOREFRONT ON THE COMMERCIAL LEVEL

On the commercial front, Japan is at the forefront. The Swiss were, for example, forced to adopt certain characteristics of Japanese clothing, less conventional than theirs. In Southeast Asia, it is the Japanese who set the tone. The strength of Japanese watchmakers also lies in their sales organization. On this point, they also imitated the methods of large Swiss companies by generalizing them and bringing them to a rare degree of perfection. It is interesting to cite here an example reported by Mr. Renggli: